By Anna Dana Helen Wood

The first half of 2018 was an eventful one on the geopolitical front. With the US-China trade war making headlines on a near daily basis, uncertainty has been bought to markets around the world including Forex. Being an essential component of Trump’s economic agenda, the administration started implementing significant changes to trade policies in 2018 in hope to reduce their long-standing trade deficit and generate jobs. After months of threats, China’s imports were targeted in July by imposing tariffs of 25% on 818 Chinese products valued at $34 billion, this has since increased to $250 billion worth of goods with the threat of $267 billion more. Of course, China has retaliated by imposing tariffs on $110 billion worth of U.S. goods and is threatening further qualitative measures that would negatively influence U.S. businesses operating in China. Nevertheless, despite accusations from Trump and other political leaders, China denies any deliberate currency manipulation that has allowed them to maintain (and improve) their bilateral trade surplus.

Trump in an interview with Reuters announced “I think China’s manipulating their currency, absolutely. And I think the euro is being manipulated also,”.

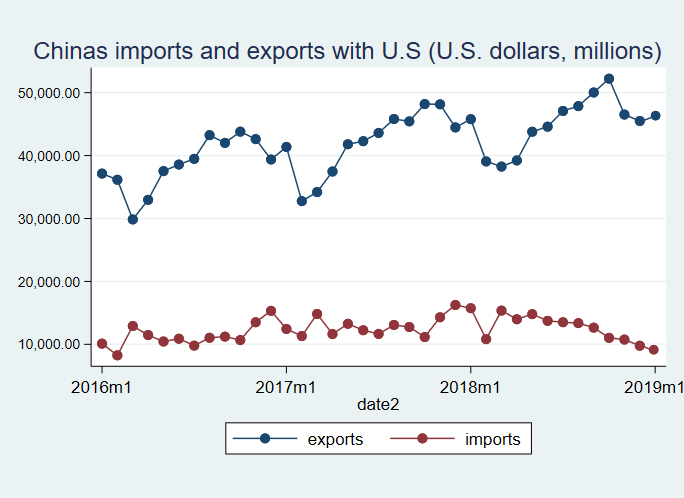

The imposition of tariffs from both countries has affected the trade flows on both sides. Basic economic theory suggests higher tariffs will reduce imports due to higher costs, thus improve trade balance. As shown in Figure 1, we can see that from June to December 2018, China’s imports from the US are gradually falling. When China revised its initial tariff list in June 2018 to now include an additional 545 products valued at $34 billion, the effects were felt by the US export sector.

Graph made on STATA. source: data.imf.org

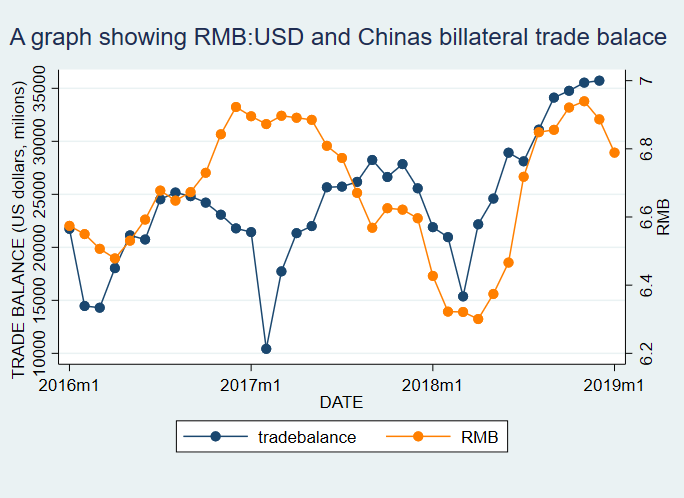

Remarkably, despite the increase in tariffs by the U.S, China’s exports have not declined since the start of 2018. It is not surprising that China’s exports increased prior to the tariff increase as U.S. firms would have anticipated higher input costs so most likely increased purchases before the imposition of tariffs. However, figure 1 depicts China’s exports gradually rising from March to November, regardless of the higher tariffs imposed by US in July. Much to surprise, this persistent rise in exports since the start of the trade war has improved China’s bilateral trade balance with the US by 60% since January 2016, depicted by the blue line in figure 2.

Graph made on STATA. source: data.imf.org and stats.bis.org

A possible reason for this is China’s exchange rate policy. China does not have a floating exchange rate that is determined by market forces like most advanced economies do. Instead it pegs its currency, the renminbi (RMB), to the U.S. dollar giving the Chinese government enormous control over the exchange rate. To mitigate pressures felt on the export sector, countries in trade wars often devalue their domestic currency. This helps offset the negative effects of increased tariffs on goods and services, preserving market share of exports abroad. The nature of China’s exchange rate makes the devaluation of the renminbi look far more deliberate than the fall in the euro during the same period. As figure 2 shows, since March 2018, the RMB has depreciated roughly 8.8% against the USD (March ’18: ¥6.32 to December ’18: ¥6.88) the weakest it’s been in 2 years. This implies that, all else being equal, China’s exports could be 8.8% cheaper in the global market. The, what is thought to be, deliberate depreciation of the renminbi has counteracted the high tariffs and made China’s prices more competitive. The ability for China to depreciate their currency has enabled them to keep net exports high, continuing to improve their current account surplus. This is supported by figure 2 which shows China’s trade balance improving at a similar rate as the RMB depreciates from November 2017 to November 2018.

China’s improving trade balance comes at the expense of a worsening U.S. deficit. While the tariffs were hoped to reduce demand of China’s imports in the U.S, in October last year Chinese goods hit a record high of $52 billion. A similar state of affairs occurred back in the 2000’s when China put downward pressure on its currency to stimulate exports and improve their trade balance. This again caused major drawbacks for many western trading countries, in particular the U.S. who already had a growing trade deficit.

When evaluating the impact of a currency fluctuation on the balance of trade we should consider the Marshall-Lerner condition. The condition states that the current account will improve after a depreciation if the sum of long-term price elasticises of demand for imports and exports is greater than 1. Although the depreciation of the RMB did cause an improvement in China’s balance of trade, figure 2 depicts a situation in which China’s trade balance improves immediately after the currency devalues in March 2018. This suggests that the Marshall-Lerner condition cannot be proved applicable in this situation as the condition does not hold in the short-run. If the Marshall-Lerner condition is a long run phenomena, the question then is: how long is the long run? Additionally, the trade war could still be considered in its early stages, making it inconclusive that the devaluation has made a permanent improvement to the trade balance in the long-run. Although it is looking very optimistic for China, the long-term effects of the RMB devaluation are still uncertain suggesting that the Marshall-Lerner condition may not hold.

Although China is running out of goods in which they can impose taxes on in retaliation, if the U.S prolongs the trade war any further China may have no choice but to continue to devalue the RMB to protect its vital export sector. If this transpires, U.S could face much bigger problems than simply cheaper Chinese goods. Countries with high national debt that are heavily reliant on exports are likely to be impacted greatly by declining prices of Chinese products in the global marketplace. This could potentially cause a chain reaction of currency devaluation throughout the world as countries are pressured to allow their currencies to weaken to avoid the risk of losing market share to Chinese firms. Depending on their willingness to battle back market forces with their foreign reserves will be a crucial factor in determining whether the US-China trade war could potentially escalate into a global currency war.